- Maslach Burnout Inventory Scoring

- Maslach Burnout Inventory Mbi Questionnaire

- Maslach Burnout Inventory (mbi Questionnaire Form

- Maslach Burnout Inventory (mbi Questionnaire Pdf

It is now clear that the Covid-19 pandemic has aggravated burnout and related forms of workplace distress, across many industries. This has led more organizations to become more aware of burnout, and more concerned about what to do about it. We felt it was the right time to assess the use of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) in organizations. This article will give an overview about what the MBI is, cover some concerning ways that it is being misused, and show how employers should use it for the benefit of employees, organizations, and the world’s understanding of burnout.

The Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) is the first scientifically developed measure of burnout and is used widely in research studies around the world. Since its first publication in 1981, the MBI.

Burnout Self-Test Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) The Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) is the most commonly used tool to self-assess whether you might be at risk of burnout. To determine the risk of burnout, the MBI explores three components: exhaustion, depersonalisation and personal achievement. Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) The Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) has been recognized for more than a decade as the leading measure of burnout, incorporating the extensive research that has been conducted in the more than 25 years since its initial publication. Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) The Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) has been recognized for more than a decade as the leading measure of burnout, incorporating the extensive research that has been conducted in the more than 25 years since its initial publication.

What Is the MBI?

As the pandemic has spilled from 2020 into 2021, so many people in so many places are talking about burnout. The phenomenon of burnout is not new — people who have been worn out and turned off by the work they do have appeared in both fictional and nonfictional writing for centuries. In the past 60 years, the term “burnout” has become a popular way of describing this particular phenomenon that captures what many people are experiencing now.

By the late 1970s, questions were crystallizing: What is the burnout experience? Why is it a problem? What causes it? Answering these questions would require research tools that did not yet exist, which led to the creation of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI). First published in 1981 and now with its Manual in its fourth edition, the MBI is the first scientifically developed measure of burnout and is used widely in research studies around the world.

The MBI aligns with the World Health Organization’s 2019 definition of burnout as a legitimate occupational experience that organizations need to address, characterized by three dimensions:

- Feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion

- Increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one’s job

- Reduced professional efficacy

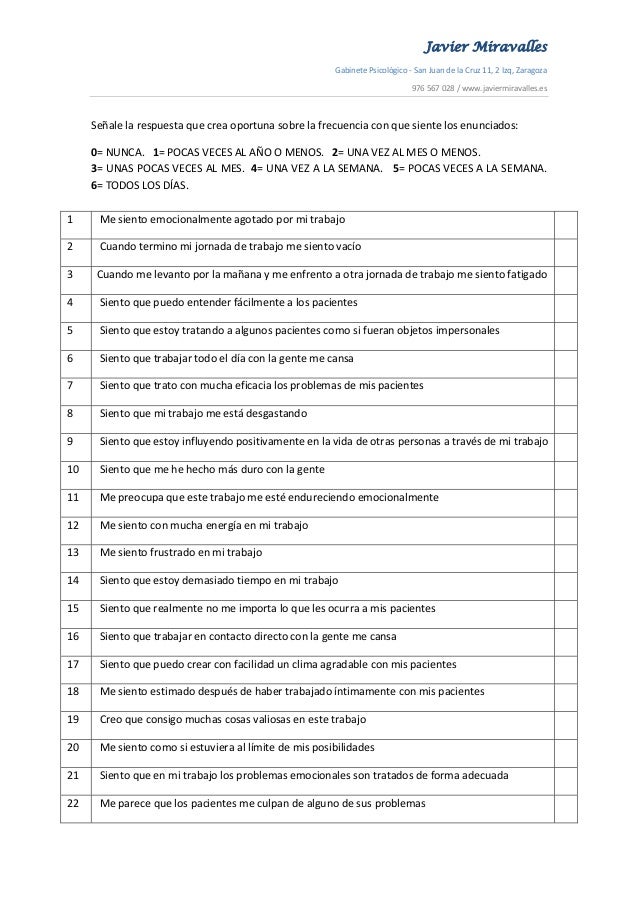

The MBI assesses each of these three dimensions of burnout separately. Its format emerged from prior exploratory work on burnout in the 1970s, which used interviews with workers in various health and human service professions, on-site observations of the workplace, and case studies. A number of consistent themes appeared in the form of statements about personal feelings or attitudes (for example, “I feel emotionally drained from my work”), so a series of these statements became the items in the MBI measure. The MBI developed an approach based on the frequency with which people experienced those feelings, with responses ranging from “never” to “every day.”

After rigorous testing, the MBI-Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS) was published, followed by other versions, including the MBI-Educators Survey (MBI-ES) and the MBI for medical personnel (MBI-MP). The MBI-General Survey (MBI-GS) was developed for use with people in any type of occupation, and was tested in several countries, in several languages.

In all versions, the MBI yields three scores for each respondent: exhaustion, cynicism, and professional efficacy. There is a continuum of frequency scores, from more positive to more negative, rather than an arbitrary dividing point between “present” and “absent.” A profile of burnout is indicated by more negative scores on all three dimensions.

Inresearchstudies, the goal has been to study what things are associated with each of the three dimensions. For example, do some types of workplace conditions make it difficult to do the job well (lower professional efficacy) or create work overload (higher exhaustion)? Does the occurrence of burnout begin with exhaustion, which then leads to cynicism and the decline in professional efficacy, or are there other paths to burnout?

Modifications and Misuses of the MBI

More recently, the MBI has been applied for other purposes, such as individual diagnosis or organizational metrics. When used correctly, these applications of the MBI can greatly benefit employees and organizations. When used incorrectly, it can result in more confusion about what burnout is rather than greater understanding. Some of these applications are even unethical.

The fact that the MBI produces three scores has led to some challenges. This complexity has led some to seek a simpler outcome by modifying the scoring procedure. First, some people have added the three scores together. The problem with this additive approach is that the same total score can be achieved by very different combinations of the three dimensions. Another misuse has been to consider the three dimensions as “symptoms” of burnout, and to then argue that a negative score on any one of these symptoms constitutes burnout. Another oversimplification has been to use only one question to assess each dimension.

Second, some people have decided to use only one of the three dimensions of burnout (usually exhaustion), implicitly proposing a new definition of burnout. In another variation of this focus on exhaustion, some have argued that the correlation with measures of depression (which contain multiple items about exhaustion) mean that burnout is really just depression.

Third, another scoring modification has involved arbitrarily dividing the sample of respondents in half and inaccurately assuming that the half that has more negative scores is burned out, and the other half is not. Some have used the descriptions of the range of scores, which divide the range into thirds (lower, mid-range, upper), as the arbitrary cutoffs for “low, medium, and high burnout.” When their study replicates that same range, they inaccurately claim that “a third of the group is highly burned out.”

What leads to all these misuses? A major reason for these scoring modifications (and resulting inaccuracies) is that many think of burnout as some sort of medical disease or disability, and they want a single score that can diagnose whether individual employees have this disability or not, yet we never designed the MBI as a tool to diagnose an individual health problem. Indeed, from the beginning, burnout was not considered some type of personal illness or disease — a viewpoint that the WHO reiterated in its May 2019 statement. However, many forms of personal therapy or treatment can only occur, or be covered by insurance, if there is an officially recognized diagnosis within the overall health-care system. There has been continuing pressure to define burnout in medical terms to make it fit within that system.

Even more troubling is the misuse of MBI scores to identify (sometimes publicly) people who are “diagnosed” as burned out and who therefore need to be dealt with in some way (“you should seek counseling,” “your team needs to shape up,” “you should quit if you can’t handle the job”). Research studies consider this nonconfidential use of MBI scores within organizations to be unethical. Given that there is no clinical basis for assuming that burnout is a personal disability, and no evidence for established treatments for it, the use of an individual’s scores in this way is clearly wrong.

Best Practices for Using the MBI at Work

The MBI was designed for discovery — both of new information that extends our knowledge about burnout and of possible strategies for change. This discovery can also take place when organizations use the MBI for practical studies and planning. When the MBI is used correctly, and in strategic combination with other relevant information, the findings can help leaders design effective ways to build engagement and establish healthier workplaces in which employees will thrive.

First, new research has revealed how to bring together all three MBI dimensions in a comprehensive and meaningful way. This new scoring procedure for the three dimensions generates five profiles of people’s work experience:

- Burnout: negative scores on exhaustion, cynicism, and professional efficacy

- Overextended: strong negative score on exhaustion only

- Ineffective: strong negative score on professional efficacy only

- Disengaged: strong negative score on cynicism only

- Engagement: strong positive scores on exhaustion, cynicism, and professional efficacy

All five of these experiences need to be better understood, not just the two extremes of burnout and engagement. When measured properly, evidence suggests that only 10% to 15% of employees fit the true burnout profile, whereas the engagement profile appears twice as often, at around 30%. That leaves over half of employees as negative in one or two dimensions — not burned out, but perhaps on the pathway there.

When research data is gathered on how people are reacting to six key components of their workplace culture (workload, control, reward, community, fairness, values — as reflected by scores on the Areas of Worklife Survey, or AWS), each profile shows a very different pattern. For example, the overextended group has just one key problem: workload (high demands and low resources). But the disengaged or ineffective groups seem to have other problems, including fairness in the workplace, or social rewards and recognition. The burnout group has major issues with multiple aspects of the workplace — a pattern that stands in sharp contrast to the “exhaustion-only” overextended group. Any solution that an employer undertakes to improve the work-life experience needs to account for the varying sources of the five different patterns, rather than assuming that one type of solution will fit all.

Second, organizations should not use the MBI in isolation. They should combine its findings with those of other tools to determine the likely causes of the five profiles. A single summary of employees’ MBI scores does not provide any useful guidance on why the summary looks like it does, nor does it suggest possible paths to improvement.

For organizations that do not have internal resources to conduct an applied study of employee burnout and engagement, an alternative option is to obtain assessment services from consultants or test publishers. External surveyors can assure confidentiality by acting as intermediaries between employee respondents and management. They often have a greater capacity to generate individual or work group reports. Large organizations do not have one overall profile on these issues: scores vary considerably across organizational units. Important questions include: What is the percentage of each profile within various units of the organization? Is burnout a problem only in certain areas or within certain occupational specialties? The organization can then use such reports to develop optimal policies and practices to effect positive change.

The online surveys for assessing burnout need to include an option for employees to provide their own written comments and suggestions. People often put a lot of thought and effort into their comments, and the results can give valuable insights, especially if themes emerge across a wide range of responses. Employers may add supplemental questions to target issues that are specific to the organization at that time.

There is an important caveat with respect to these kinds of organizational assessments: organizations must share the results with the people who generated them. All too often, we have seen leaders collect information from their employees but never provide any feedback about what they learned and whether they will actually use that information for positive improvements. When employees do work that is not acknowledged, the risk of cynicism and frustration rises. It is important for leaders to reflect on the implications of the pattern of scores and the themes of the comments. Management at all levels has to clearly communicate the importance of the organizational assessment; the goal is to make positive change, and management will take action.

“Burnout” has become a popular umbrella term for whatever distresses people in their work, but we hope we’ve cleared up some misconceptions. Although the label can be misused and misunderstood, it is an important red-flag warning that things can go wrong for employees on the job. That warning should not be ignored or downplayed but should incite course corrections. All stakeholders from line workers to the boardroom need a complete understanding of what burnout is and how it can be properly identified and successfully managed; this is essential to reshaping today’s workplaces and designing better ones in the future.

Maslach Burnout Inventory Scoring

This article is adapted from the HBR Guide to Beating Burnout.

| Maslach Burnout Inventory | |

|---|---|

| Purpose | introspective psychological inventory pertaining to occupational burnout |

The Maslach Burnout Inventory(MBI) is a psychological assessment instrument comprising 22 symptom items pertaining to occupational burnout.[1] The original form of the MBI was developed by Christina Maslach and Susan E. Jackson with the goal of assessing an individual's experience of burnout.[2] The instrument takes 10 minutes to complete.[3] The MBI measures three dimensions of burnout: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization,[a] and personal accomplishment.[1]

Following the publication of the MBI in 1981, new versions of the MBI were gradually developed to apply to different groups and different settings.[1] There are now five versions of the MBI: Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS), Human Services Survey for Medical Personnel (MBI-HSS (MP)), Educators Survey (MBI-ES), General Survey (MBI-GS),[4] and General Survey for Students (MBI-GS [S]).[1]

Two meta-analyses of primary studies that report sample-specific reliability estimates for the three MBI scales found that emotional exhaustion scale has good enough reliability; however, reliability is problematic regarding depersonalization and personal accomplishment scales.[5][6] Research based on the job demands-resources (JD-R) model[7] indicates that the emotional exhaustion, the core of burnout, is directly related to demands and inversely related to the extensiveness of resources.[8][9][10] The MBI has been validated for human services populations,[11][12][13][14] educator populations,[15][16][17] and general work populations.[18][19][20][21][22]

The MBI is often combined with the Areas of Worklife Survey (AWS) to assess levels of burnout and worklife context.[23]

Uses of the Maslach Burnout Inventory[3][edit]

- Assess professional burnout in human service, education, business, and government professions.

- Assess and validate the three-dimensional structure of burnout.

- Understand the nature of burnout for developing effective interventions.

Maslach Burnout Inventory Scales[1][edit]

Emotional Exhaustion (EE)[edit]

The 9-item Emotional Exhaustion (EE) scale measures feelings of being emotionally overextended and exhausted by one's work. Higher scores correspond to greater experienced burnout. This scale is used in the MBI-HSS, MBI-HSS (MP), and MBI-ES versions.

The MBI-GS and MBI-GS (S) use a shorter 5-item version of this scale called 'Exhaustion'.

Depersonalization (DP)[edit]

The 5-item Depersonalization (DP) scale measures an unfeeling and impersonal response toward recipients of one's service, care, treatment, or instruction. Higher scores indicate higher degrees of experienced burnout. This scale is used in the MBI-HSS, MBI-HSS (MP) and the MBI-ES versions.

Personal Accomplishment (PA)[edit]

The 8-item Personal Accomplishment (PA) scale measures feelings of competence and successful achievement in one's work. Lower scores correspond to greater experienced burnout. This scale is used in the MBI-HSS, MBI-HSS (MP), and MBI-ES versions.

Cynicism[edit]

The 5-item Cynicism scale measures an indifference or a distance attitude towards one's work. It is akin to the Depersonalization scale. The cynicism measured by this scale is a coping mechanism for distancing oneself from exhausting job demands. Higher scores correspond to greater experienced burnout. This scale is used in the MBI-GS and MBI-GS (S) versions.

Professional Efficacy[edit]

The 6-item Professional Efficacy scale measures feelings of competence and successful achievement in one's work. It is akin to the Personal Accomplishment scale. This sense of personal accomplishment emphasizes effectiveness and success in having a beneficial impact on people. Lower scores correspond to greater experienced burnout. This scale is used in the MBI-GS and MBI-GS (S) versions.

Forms of the Maslach Burnout Inventory[1][edit]

The MBI has five validated forms composed of 16-22 items to measure an individual's experience of burnout.

Maslach Burnout Inventory - Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS)[edit]

The MBI-HSS consists of 22 items and is the original and most widely used version of the MBI. It was designed for professionals in human services and is appropriate for respondents working in a diverse array of occupations, including nurses, physicians, health aides, social workers, health counselors, therapists, police, correctional officers, clergy, and other fields focused on helping people live better lives by offering guidance, preventing harm, and ameliorating physical, emotional, or cognitive problems. The MBI-HSS scales are Emotional Exhaustion, Depersonalization, and Personal Accomplishment.

Maslach Burnout Inventory - Human Services Survey for Medical Personnel (MBI-HSS (MP))[edit]

The MBI-HSS (MP) is a variation of the MBI-HSS adapted for medical personnel. The most notable alteration is this form refers to 'patients' instead of 'recipients'. The MBI-HSS (MP) scales are Emotional Exhaustion, Depersonalization, and Personal Accomplishment.

Maslach Burnout Inventory - Educators Survey (MBI-ES)[edit]

The MBI-ES consists of 22 items and is a version of the original MBI for use with educators. It was designed for teachers, administrators, other staff members, and volunteers working in any educational setting. This form was formerly known as MBI-Form Ed. The MBI-ES scales are Emotional Exhaustion, Depersonalization, and Personal Accomplishment.

Maslach Burnout Inventory - General Survey (MBI-GS)[edit]

The MBI-GS consists of 16 items and is designed for use with occupational groups other than human services and education, including those working in jobs such as customer service, maintenance, manufacturing, management, and most other professions. The MBI-GS scales are Exhaustion, Cynicism, and Professional Efficacy.

Maslach Burnout Inventory - General Survey for Students (MBI-GS (S))[edit]

The MBI-GS (S) is an adaptation of the MBI-GS designed to assess burnout in college and university students. It is available for use but its psychometric properties are not yet documented. The MBI-GS (S) scales are Exhaustion, Cynicism, and Professional Efficacy.

Scoring the Maslach Burnout Inventory[edit]

All MBI items are scored using a 7 level frequency ratings from 'never' to 'daily.' The MBI has three component scales: emotional exhaustion (9 items), depersonalization (5 items) and personal achievement (8 items). Each scale measures its own unique dimension of burnout. Scales should not be combined to form a single burnout scale. Maslach, Jackson, and Leiter[1] described item scoring from 0 to 6. There are score ranges that define low, moderate and high levels of each scale based on the 0-6 scoring.

The 7-level frequency scale for all MBI scales is as follows:

Examples of use[edit]

The Maslach Burnout Inventory has been used in a variety of studies to study burnout, including with health professionals[24][25] and teachers.[26][27]

Notes[edit]

- ^The term 'depersonalization' as used by Maslach and Jackson should not be confused with the same term used in psychiatry and clinical psychology as a hallmark of dissociative disorder.

Maslach Burnout Inventory Mbi Questionnaire

References[edit]

Maslach Burnout Inventory (mbi Questionnaire Form

- ^ abcdefgMaslach, C.; Jackson, S.E.; Leiter, M.P. (1996–2016). Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual (Fourth ed.). Menlo Park, CA: Mind Garden, Inc.

- ^Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. (1981). 'The measurement of experienced burnout'. Journal of Occupational Behavior. 2 (2): 99–113. doi:10.1002/job.4030020205.

- ^ ab'Maslach Burnout Inventory Product Specs'. www.mindgarden.com. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- ^Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P. & Kalimo, R. (1995, September). The Maslach Burnout Inventory—General Survey: A self-report questionnaire to assess burnout at the workplace. In M. P. Leiter, Extending the Burnout Construct: Reflecting Changing Career Paths. Symposium, APA/NIOSH conference, Work, Stress, and Health '95: Creating a Healthier Workplace. Washington, DC.

- ^Aguayo, R., Vargas, C., de la Fuente, E. I., & Lozano, L. M. (2011). 'A meta-analytic reliability generalization study of the Maslach Burnout Inventory'(PDF). International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology. 11.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^Wheeler, D.L; Vassar, M.; Worley, J.A.; Barnes, L.B. (2011). 'A reliability generalization meta-analysis of coefficient alpha for the Maslach Burnout Inventory'. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 71: 231–244. doi:10.1177/0013164410391579. hdl:10983/15305. S2CID143330660.

- ^Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. (2001). 'The Job Demands-Resources Model of Burnout'. Journal of Applied Psychology. 86 (3): 499–512. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499. PMID11419809.

- ^Lee, R. T. & Ashforth, B. E. (1996). A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of job burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81: 123-133.

- ^Alarcon, G.M. (2011). 'A meta-analysis of burnout with job demands, resources, and attitudes'. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 79 (2): 549–562. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2011.03.007.

- ^Crawford, E. R.; LePine, J. A.; Rich, B. L. (2010). 'Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test'. Journal of Applied Psychology. 95 (5): 834–848. doi:10.1037/a0019364. PMID20836586.

- ^Ahola, K.; Hakenen, J. (2007). 'Job strain, burnout, and depressive symptoms: A prospective study among dentists'. Journal of Affective Disorders. 104 (1–3): 103–110. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2007.03.004. PMID17448543.

- ^Gil-Monte, P. R. (2005). 'Factorial validity of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI-HSS) among Spanish professionals'. Revista de Saude Publica. 39 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1590/s0034-89102005000100001. PMID15654454.

- ^Maslach, C. & Jackson, S. E. (1982). Burnout in health professions: A social psychological analysis. In G. Sanders & J. SuIs (Eds.), Social psychology of health and illness. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- ^Poghosyan, L.; Aiken, L. H.; Sloane, D. M. (2009). 'Factor structure of the Maslach Burnout Inventory: An analysis of data from large scale cross-sectional surveys of nurses from eight countries'. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 46 (7): 894–902. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.03.004. PMC2700194. PMID19362309.

- ^Byrne, B. M. (1993). 'The Maslach Burnout Inventory: Testing for factorial validity and invariance across elementary, intermediate and secondary teachers'. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 66 (3): 197–212. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8325.1993.tb00532.x.

- ^Gold, Y. (1984). The factorial validity of the Maslach Burnout Inventory in a sample of California elementary and junior high school classroom teachers. Educational and Psychological Measurement,44: 1009-1016.

- ^Kokkinos, C. M. (2006). 'Factor structure and psychometric properties of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Educators Survey among elementary and secondary school teachers in Cyprus'. Stress and Health. 22 (1): 25–33. doi:10.1002/smi.1079.

- ^Iwanicki, E. F.; Schwab, R. L. (1981). 'A cross-validational study of the Maslach Burnout Inventory'. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 41 (4): 1167–1174. doi:10.1177/001316448104100425. S2CID143358113.

- ^Leiter, M. P. & Schaufeli, W. B. (1996). Consistency of the burnout construct across occupations. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 9: 229–243.

- ^Richardsen, A. M.; Martinussen, M. (2005). 'Factorial validity and consistency of the MBI-GS across occupational groups in Norway'. International Journal of Stress Management. 12 (3): 289–297. doi:10.1037/1072-5245.12.3.289.

- ^Schaufeli, W. B.; Salanova, M.; Bakker, A. B.; Gonzalez-Roma, V. (2002). 'The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J'. Journal of Happiness Studies. 3: 71–92. doi:10.1023/A:1015630930326. S2CID33735313.

- ^Schutte, N.; Toppinen, S.; Kalimo, R.; Schaufeli, W. B. (2000). 'The factorial validity of the Maslach Burnout Inventory - General Survey (MBI-GS) across occupational groups and nations'. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 73: 53–66. doi:10.1348/096317900166877.

- ^Leiter, M.P.; Maslach, C. (1999). 'Six areas of worklife: A model of the organizational context of burnout'. Journal of Health and Human Resources Administration. 21: 472–489.

- ^Taylor, Cath; Graham, Jill; Potts, Henry WW; Richards, Michael A; Ramirez, Amanda J (2005). 'Changes in mental health of UK hospital consultants since the mid-1990s'. The Lancet. 366 (9487): 742–744. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(05)67178-4. PMID16125591. S2CID11391979.

- ^Firth, Hugh; McIntee, Jean; McKeown, Paul; Britton, Peter G. (1985). 'Maslach Burnout Inventory: Factor Structure and Norms for British Nursing Staff'. Psychological Reports. 57 (1): 147–150. doi:10.2466/pr0.1985.57.1.147. PMID4048330. S2CID1417252.

- ^Evers, Will J. G.; Brouwers, André; Tomic, Welko (2002). 'Burnout and self-efficacy: A study on teachers' beliefs when implementing an innovative educational system in the Netherlands'. British Journal of Educational Psychology. 72 (2): 227–243. doi:10.1348/000709902158865. hdl:1820/1221. PMID12028610.

- ^Milfont, Taciano L.; Denny, Simon; Ameratunga, Shanthi; Robinson, Elizabeth; Merry, Sally (2007). 'Burnout and Wellbeing: Testing the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory in New Zealand Teachers'. Social Indicators Research. 89: 169–177. doi:10.1007/s11205-007-9229-9. S2CID144387347.

Comments are closed.